|

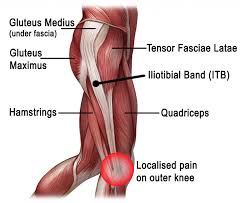

Iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS) has been reported as the second most common running injury and most common reason for lateral (outer) knee pain in runners. In case you were wondering, a large research study reported patellofemoral pain syndrome to be the most common running-related injury. What is your ITB? The iliotibial band is a thick band of fascia that runs on the outer side of the thigh. It is a dynamic and multidimensional structure with relationships that span the lumbar spine (lower back) to the anterolateral (front and outer) aspect of the knee. The ITB connects through the gluteus maximus to the lumbar fascial tissue; and down to the femur (thigh bone), the outer quadriceps muscle (vastus lateralis), the outer hamstring muscle (biceps femoris), and anterolateral tibia (shin bone). The interactions of the ITB suggest an interactive relationship between these different structures. Diagnosis and Typical Symptoms The diagnosis of ITBS is based on clinical examination – patients typically present with tenderness over the lateral femoral epicondyle and report a sharp, burning pain when the practitioner presses on the lateral epicondyle during knee flexion and extension. The pain is particularly acute when the knee is at 30° of flexion. The onset often occurs at the lateral knee after a few miles of running, or hiking long distances. Walking with the knee extended can relieve the symptoms, and downhill walking or running can aggravate symptoms. Theories and Causes There are two main theories behind ITBS: the compression model and the friction model. The ITB inserts in the region of the femoral epicondyle and it glides over the lateral femoral epicondyle when the knee bends. It is thought that due to biomechanical imbalances, the ITB can either become compressed or there is increased frictioning (rubbing) which causes pain and inflammation. Scientific literature often suggests there is there an overlap between these two models. There is no one single cause of ITBS in runners, however, research has shown that biomechanical factors such as increased hip adduction (movement towards your mid-line), knee internal rotation, and femur (thigh bone) external rotation can contribute. Muscle weakness in the hip abductor and/or external rotators can be involved, as well altered neuromuscular control, or poor running technique leading to pelvic drop or rotation. This highlights how ITBS is actually preceded by numerous biomechanical issues, and that the lateral knee pain itself is often the end symptom that you become aware of. On a positive note, these biomechanical issues have the potential to be corrected with physiotherapy, and this also emphasises the importance of sound biomechanics in the first place, which can help to prevent these types of running injuries. Your physiotherapist can help to reduce your injury risk by assessing your movement control and providing you with a plan to improve your biomechanics. Management One key biomechanical goal is to reduce strain related to excessive lengthening of the ITB and stress related to the insertion at the lateral femoral epicondyle. In the initial stages (up to 2-weeks), anti-inflammatory medication and ice is recommended, along with a reduction in your running volume and intensity, and avoid downhill running. Physiotherapy manual treatment for ITBS may include myofascial treatment addressing trigger points in the biceps femoris, vastus lateralis, gluteus maximus, and tensor fasciae latae muscles. In addition, acupuncture/dry needling techniques can prove helpful. Physiotherapy will also aim to address walking and running re-training, particularly looking to correct pelvic drop, pelvic rise, and trunk deviation if present. ITB stretches can be useful, but you may also need to stretch various muscle groups around the hip and pelvis, such as the quadriceps, gluteals or hamstrings (if appropriate). Core strengthening exercises (particularly gluteus medius exercises) and progressive resistance exercises will be given to improve biomechanics and motor control. Movement control tests such as the single leg squat, the step down test, and single leg dead lift can help to provide baseline measures from which to improve. If localised pain persists at the lateral femoral epicondyle, an ultrasound-guided corticosteroid injection could be considered. You can discuss this further with your physiotherapist. Return to Running When your exercises are pain-free and you can achieve them with good form, this is a good indication that running can be recommenced. A guideline for this is 6-weeks though the range is variable based on successful completion of the earlier phases of recovery. Graded progression is achieved by running every other day with emphasis on good running form, and initially may include easy sprints on level ground. Downhill running is not recommended in the first 2-weeks, and an emphasis on movement control is recommended to focus on pelvic control, forward trunk, and softer landing. Should you wish to discuss any aspects of this or book an appointment with one of our therapists please get in touch. References

Baker, R. L. and Fredericson, M. 2016. Iliotibial Band Syndrome in Runners: Biomechanical Implications and Exercise Interventions. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 27(1), pp. 53-77. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2015.08.001 Fairclough, J. et al. 2006. The functional anatomy of the iliotibial band during flexion and extension of the knee: implications for understanding iliotibial band syndrome. Journal of Anatomy 208(3), pp. 309-316. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00531.x Taunton, J. E. et al. 2002. A retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuries. Br J Sports Med 36(2), pp. 95-101. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.36.2.95

2 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorPhysioimpulse Chartered Physiotherapists Archives

June 2024

|

Services |

Get in Touch

|

©

RSS Feed

RSS Feed