Patella femoral joint pain (PFJP) commonly known as Runner's Knee The PFJ is the joint at the front of the knee connecting the patella (knee cap) and the femur (thigh bone). Pain can emanate from many structures, most commonly the bony surfaces and associated tendons. Risk factors

Signs and symptoms Patients with PFJ pain experience pain on the anterior aspect (front) of the knee. Patients usually experience an ache that may increase to a sharper pain with activity. Pain is typically experienced during activities that bend or straighten the knee repetitively particularly whilst weight bearing, such as running or squatting in the gym. Pain may be worse first thing in the morning or following activity (once the body has cooled down). This may be associated with knee stiffness and can sometimes cause the patient to limp. Clinical signs Patients with PFJP typically experience pain when firmly touching the distal aspect of the patella and the patellar tendon and also mobilising the patella. In more severe cases, swelling may be present at the anterior aspect of the knee along with an associated grinding sound when bending or straightening the knee. Occasionally, patients may also experience episodes of the knee giving way or collapsing due to pain. Investigations A thorough subjective and objective examination from a physiotherapist is sufficient to diagnose PFJP. Investigations such as an ultrasound or MRI may be used to assist with diagnosis. Management options Physiotherapy treatment for PFJ is vital to speed up the recovery process, ensure an optimal outcome and reduce the likelihood of recurrence. Treatment options include:

Here are some exercises you can try to improve balance, strength and control. Aim to keep hips, knees and knees aligned with minimal wobble! If these do not help then give us a call for an in-depth assessment!

0 Comments

Did you know?

The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy have come up with some top tips to help with your desk environment: Recent debate has argued that there is no perfect posture and that frequent breaks and regular exercise is the key:

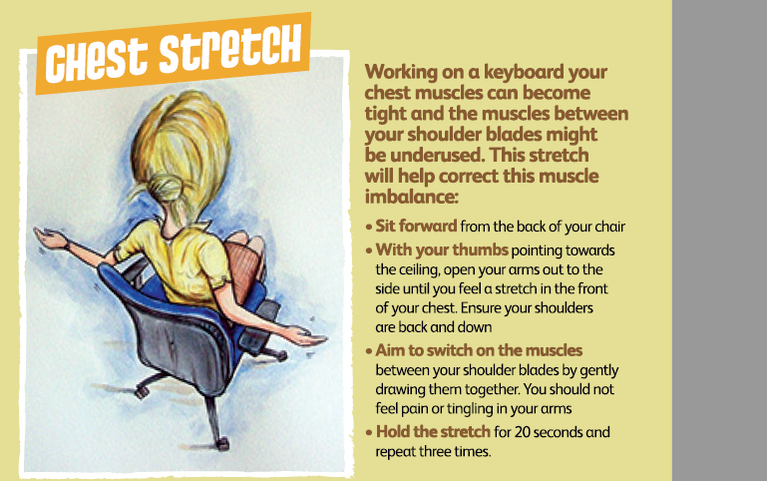

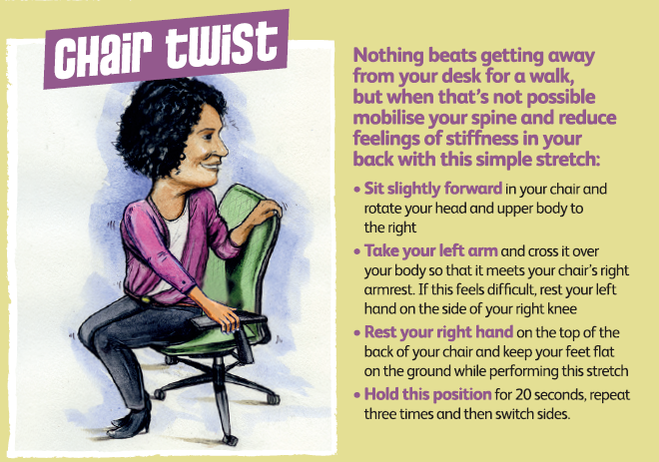

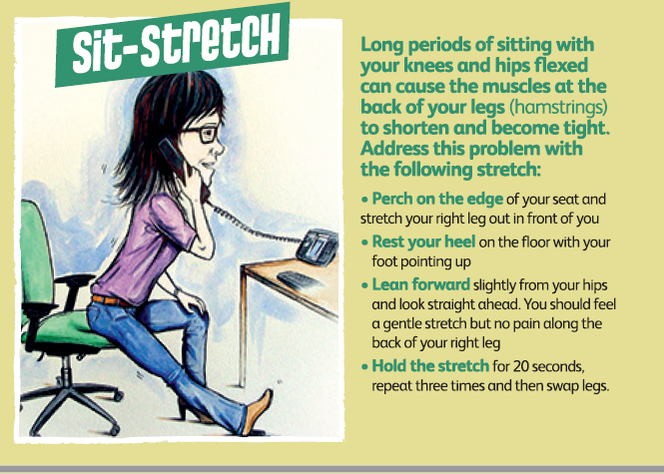

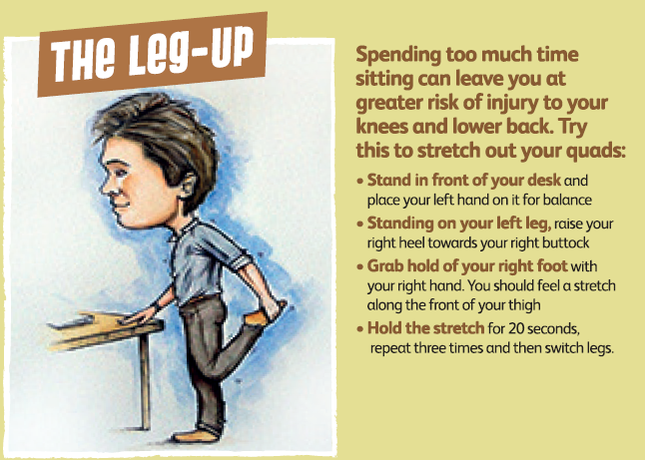

These simple stretches can help ease the aches and pains associated with sitting for long periods combined with regular physical activity: If you try all these exercise and continue to suffer work related aches and pains then give us a call for some extra input from our physio team.

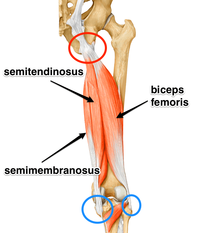

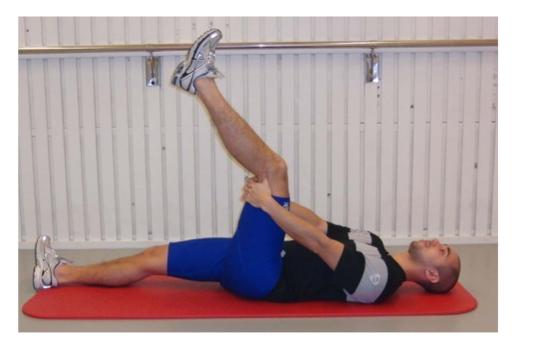

The hamstrings are formed by three muscles and their tendons. The hamstrings arise from the ischial tuberosity, or sitting bones, at the bottom of your pelvis. They run down the back of your thigh and their tendons cross the knee joint and attach onto each side of the shin bone (tibia). The hamstrings are involved in hip extension (moving the leg backwards) and knee flexion (bending the knee). Acute hamstring injuries are common and generally present with localised pain following rapid acceleration or deceleration movements, such as when sprinting, and frequently occur in sports such as football, skiing, and hockey, to name a few. Acute injuries can also occur when the muscle is stretched too far Whereas chronic/persistent hamstring injuries present with a stealthy onset of unrelenting pain made worse with sports activities and sitting – often found in runners. It is very important to treat and rehabilitate hamstring injuries correctly; incorrect or improper healing makes re-injury more likely. For the first 3 to 5 days (in the acute phase), the general consensus is to control swelling, pain and bleeding. The POLICE method is often used. POLICE stands for Protection, Optimal Loading, Ice, Compression and Elevation. Following this acute phase, there was previously some ambiguity among treatment protocols until the introduction of Askling and colleagues’ 2013 research. In this paper, Carl Askling and colleagues used 75 elite Swedish football players to compare two different hamstring rehabilitation protocols called the C-Protocol and L-Protocol. They then assessed outcomes of return to play and re-injury. The L-Protocol focused on eccentric loading of the hamstrings while the C-protocol consisted of conventional hamstring rehabilitation exercises. Participants in the L-protocol (outlined below) were able to return to sport significantly faster than those in the conventional group (mean 28 days vs 52 days). Their research into which protocol was best for chronic injuries was inconclusive, but the researchers were able to surmise that rehabilitation protocols consisting of eccentric exercises are more effective in returning athletes to their sports following hamstring injury. Additionally, it is recommended that hamstring injury rehabilitation protocols should be preferentially based on strength and flexibility exercises that primarily involve exercises with high loads at long muscle–tendon lengths. The L- Protocol Exercises

These exercises are a great starting point. Head over to our clinics for this and much more in the way of hamstring treatment, rehabilitation and general advice. We can also use hands on manual therapy of the hip and spine in combination with exercise therapy to help you recover and rehabilitate fully.

Good luck and keep active! Chris, PhysioImpulse |

AuthorPhysioimpulse Chartered Physiotherapists Archives

June 2024

|

Services |

Get in Touch

|

©

RSS Feed

RSS Feed